Structural Soil An Innovative Medium Under Pavement

Have you ever wondered how on earth trees grow in little square planters alongside roadways and sidewalks?

Unless you are one of the few in the know, you probably have. An education on structural soil help will help explain how growing trees below pavement is possible and how it provides urban areas opportunity to enhance the green space within city limits.

Here’s a great article from Cornell University that helps highlight the composition and uses of structural soil. There is a ton of valuable and informative information here, we hope you enjoy it as much as we did.

Here’s a great article from Cornell University that helps highlight the composition and uses of structural soil. There is a ton of valuable and informative information here, we hope you enjoy it as much as we did.

Read the full article here.

Introduction

The major impediment to establishing trees in paved urban areas is the lack of an adequate volume of soil for tree root growth. Soils under pavements are highly compacted to meet load-bearing requirements and engineering standards. This often stops roots from growing, causing them to be contained within a very small useable volume of soil without adequate water, nutrients or oxygen. Subsequently, urban trees with most of their roots under pavement grow poorly and die prematurely. It is estimated that an urban tree in this type of setting lives for an average of only 7-10 years, where we could expect 50 or more years with better soil conditions. Those trees that do survive within such pavement designs often interfere with pavement integrity. Older established trees may cause pavement failure when roots grow directly below the pavement and expand with age. Displacement of pavement can create a tripping hazard. As a result, the potential for legal liability compounds expenses associated with pavement structural repairs. Moreover, pavement repairs which can significantly damage tree roots often result in tree decline and death.

The problems as outlined above do not necessarily lie with the tree installation but with the material below the pavement in which the tree is expected to grow. New techniques for meeting the often opposing needs of the tree and engineering standards are needed. One new tool for urban tree establishment is the redesign of the entire pavement profile to meet the load-bearing requirement for structurally sound pavement installation while encouraging deep root growth away from the pavement surface. The new pavement substrate, called ‘structural soil’, has been developed and tested so that it can be compacted to meet engineering requirements for paved surfaces, yet possess qualities that allow roots to grow freely, under and away from the pavement, thereby reducing sidewalk heaving from tree roots.

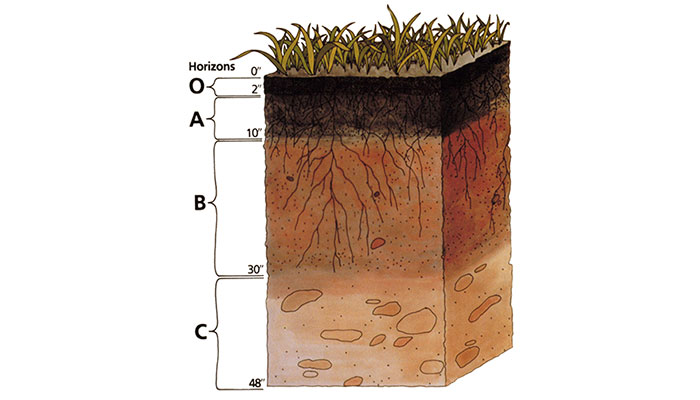

Convential Tree Pits are Designed for Failure Looking at a typical street tree pit detail, it is evident that it disrupts the layered pavement system. In a sidewalk pavement profile, a properly compacted subgrade of existing material often is largely impermeable to root growth and water infiltration and significantly reduces drainage if large percentages of sand are not present. Above the subgrade there is usually a structural granular base material. To maintain a stable pavement surface the base material is well compacted and possesses high bearing strength. This is why a gravel or sand material containing little silt or clay is usually specified and compacted to 95% Proctor density (AASHTO T-99). The base layer is granular material with no appreciable plant available moisture or nutrient holding capacity. Subsequently, the pavement surrounding the tree pit is designed to repel or move water away, not hold it, since water just below the pavement can cause pavement failure. Acknowledging that; the above generalizations do not account for all of the challenges below the pavement for trees, it is no mystery why trees are often doomed to failure before they are even planted.

The subgrade and granular base course materials are usually compacted to levels associated with root impedance. Given the poor drainage below the base course, the tree often experiences a largely saturated planting soil. Designed tree pit drainage can relieve soil saturation, but does nothing to relieve the physical impedance of the material below the pavement which physically stops root growth.

A New System to Integrate Trees and Pavement

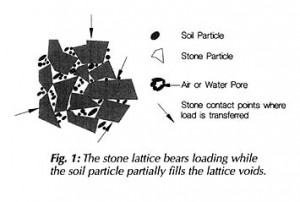

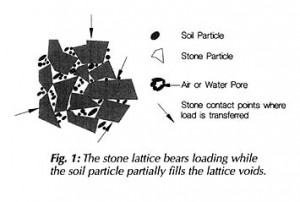

‘Structural soil’ is a designed medium which can meet or exceed pavement design and installation requirements while remaining root penetrable and supportive of tree growth. Cornell’s Urban Horticulture Institute, has been testing a series of materials over the past five years focused on characterizing their engineering as well as horticultural properties. The materials tested are gap-graded gravels which are made up of crushed stone, clay loam, and a hydrogel stabilizing agent. The materials can be compacted to meet all relevant pavement design requirements yet allow for sustainable root growth. The new system essentially forms a rigid, load-bearing stone lattice and partially fills the lattice voids with soil (Figure 1). Structural soil provides a continuous base course under pavements while providing a material for tree root growth. This shifts designing away from individual tree pits to an integrated, root penetrable, high strength pavement system.

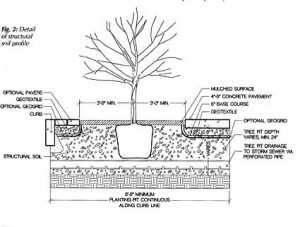

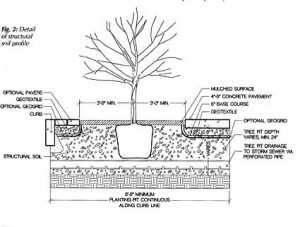

This system consists of a four to six inch rigid pavement surface, with a pavement opening large enough to accommodate a forty year or older tree (Figure 2) .

The opening could also consist of concentric rings of interlocking pavers designed for removal as the buttress roots meet them. Below that, a conventional base course could be installed and compacted with the material meeting normal regional pavement specifications for the traffic they are expected to experience. The base course would act as a root exclusion zone from the pavement surface. Although field tests show that tree roots naturally tend to grow away from the pavement surface in structural soil. A geotextile could segregate the base course of the pavement from the structural soil. The gap-graded, structural soil material has been shown to allow root penetration when compacted. This material would be compacted to not less than 95% Proctor density (AASHTO T-99) and possess a California Bearing Ratio greater than 40 [Grabosky and Bassuk 1995,1996]. The structural soil thickness would depend on the designed depth to subgrade or to a preferred depth of 36 inches. This depth of excavation is negotiable, but a 24 inch minimum is encouraged for the rooting zone. The subgrade should be excavated to parallel the finished grade. Under-drainage conforming to approved engineering standards for a given region must be provided beneath the structural soil material.

The structural soil material is designed as follows. The three components of the structural soil are mixed in the following proportions by weight, crushed stone: 100; clay loam: 20; hydrogel: 0.03. Total moisture at mixing should be 10% (AASHTO T-99 optimum moisture).

The structural soil material is designed as follows. The three components of the structural soil are mixed in the following proportions by weight, crushed stone: 100; clay loam: 20; hydrogel: 0.03. Total moisture at mixing should be 10% (AASHTO T-99 optimum moisture).

Crushed stone (granite or limestone) should be narrowly graded from 3/4 -1 1/2 inch, highly angular with no fines. The clay loam should conform to the USDA soil classification system (gravel <5%, sand 25-30%, silt 20-40%, clay 25-40%). Organic matter should range between 2% and 5%. The hydrogel, a potassium propenoate-propenamide copolymer is added in a small amount to act as a tackifier, preventing separation of the stone and soil during mixing and installation. Mixing can be done on a paved surface using front end loaders. Typically the stone is spread in a layer, the dry hydrogel is spread evenly on top and the screened moist loam is the top layer. The entire pile is turned and mixed until a uniform blend is produced. The structural soil is then installed and compacted in 6 inch lifts.

In a street tree installation of such a structural soil, the potential rooting zone could extend from building face to curb, running the entire length of the street. This would ensure an adequate volume of soil to meet the long term needs of the tree. Where this entire excavation is not feasible, a trench, running continuous and parallel to the curb, eight feet wide and three feet deep would be minimally adequate for continuous street tree planting.

There will be a need to ensure moisture recharge and free gas exchange throughout the root zone. The challenge may be met by the installation of a three dimensional geo-composite (a geo-grid wrapped in textile one inch thick by eight inches wide) which could be laid above the structural soil as spokes radiating from the trunk flair opening. This is currently in the testing stage. Other pervious surface treatments could also provide additional moisture recharge, as could traditional irrigation.

When compared to existing practice, additional drainage systems, and the redesigned structural soil layer represent additional costs to a project. The addition of the proposed structural soil necessitates deeper excavation of the site which also may be costly. In some regions this excavation is a matter of standard practice. However, this process might best be suited for new construction and infrastructure replacement or repair, since the cost of deep excavation is already incurred.

The Urban Horticulture Institute continues to work on refining the specification for producing a structural soil material to make the system cost effective. It is patent pending and will be sold with the trademark ‘CU-Soil’ to insure quality control. Testing over five years has demonstrated that stabilized, gap-graded structural soil materials can meet this need while allowing rapid root penetration. Several working installations have been completed in lthaca, NY, New York City, NY, Cincinnati, OH, Cambridge, MA and elsewhere. To date, the focus has been on the use of these mixes to greatly expand the potential rooting volume under pavement. It appears that an added advantage of using a structural soil is its ability to allow roots to grow away from the pavement surface, thus reducing the potential for sidewalk heaving as well as providing for healthier, long-lived trees.

by

Nina Bassuk, Director and Professor Urban Horticulture Institute, Cornell University, lthaca, NY

Jason Grabosky, Urban Horticulture Institute, Cornell University, lthaca, NY

Peter Trowbridge, FASLA, Professor Landscape Architecture, Cornell University, lthaca, NY

James Urban, FASLA, James Urban and Associates, Annapolis, MD

Save

Tom says, “Dirt is the stuff underneath your fingernails, whereas soil is an engineered composition of organic matter (sand, clay and organic matter) designed specifically for your project’s grow medium and geographic location.” As we dive into the different topics, please feel free to ask your questions in the comments or via email/web form. We would love to interact with you once we get things rolling. We want this series to be helpful to those in our geographic region.

Tom says, “Dirt is the stuff underneath your fingernails, whereas soil is an engineered composition of organic matter (sand, clay and organic matter) designed specifically for your project’s grow medium and geographic location.” As we dive into the different topics, please feel free to ask your questions in the comments or via email/web form. We would love to interact with you once we get things rolling. We want this series to be helpful to those in our geographic region.

Here’s a great article from Cornell University that helps highlight the composition and uses of structural soil. There is a ton of valuable and informative information here, we hope you enjoy it as much as we did.

Here’s a great article from Cornell University that helps highlight the composition and uses of structural soil. There is a ton of valuable and informative information here, we hope you enjoy it as much as we did.

The structural

The structural